Listening to the place before designing for it

The best design work starts with deep listening. Before drawings, there are conversations - often dozens of them - about identity, ownership and memory. What one group sees as a proud moment might be a painful chapter for another. Getting this wrong can fracture trust before the doors even open.

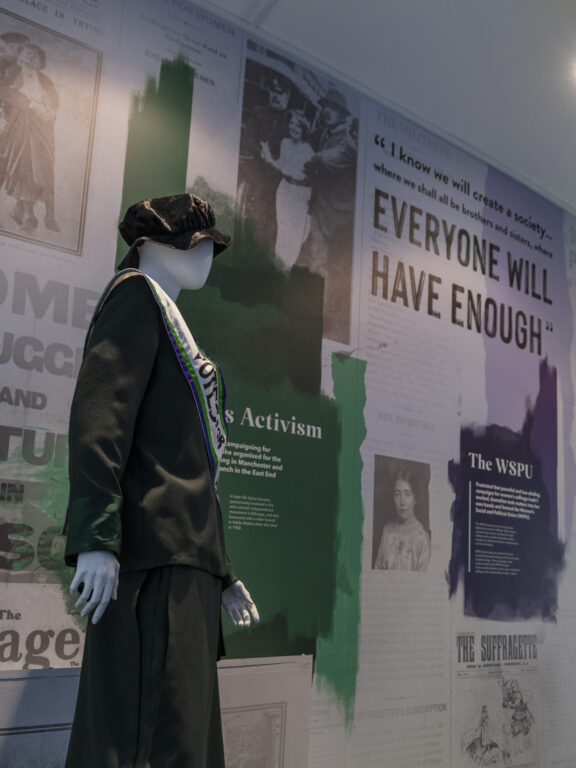

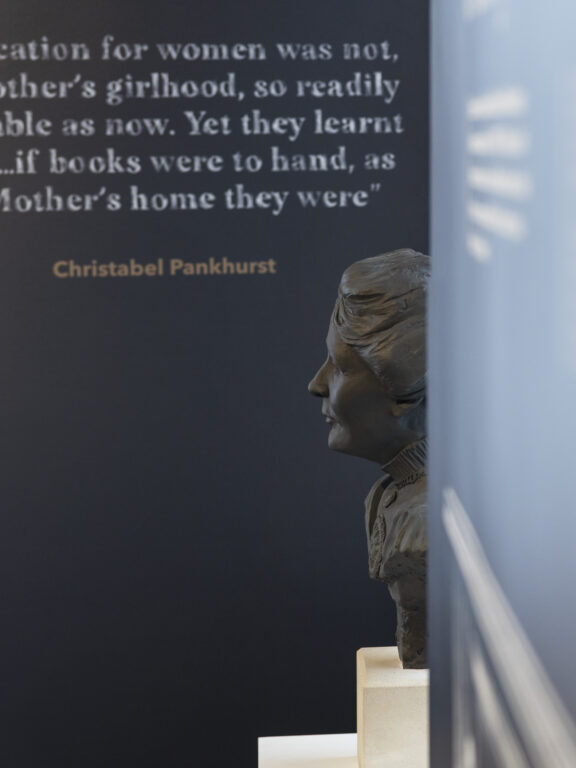

The Pankhurst Centre in Manchester is a clear example of design shaped by listening. Interpreting the former home of Emmeline Pankhurst, where the suffragette movement began, required care. The challenge was not just to tell a feminist story, but to show the domestic reality of the women who built it. The building itself had to speak.

Design decisions at the Centre reflect that duality - intimate, homely textures sit beside bold, rallying statements -personal letters and objects share space with political slogans. It’s a reminder that ‘place’ isn’t only geography, it’s also emotional territory too. When museums sit within living communities, design becomes diplomacy as much as creativity. The process of inclusion matters as much as the outcome - local involvement in shaping narrative, imagery and language makes the final space feel earned, not imposed.

Building unity from complexity

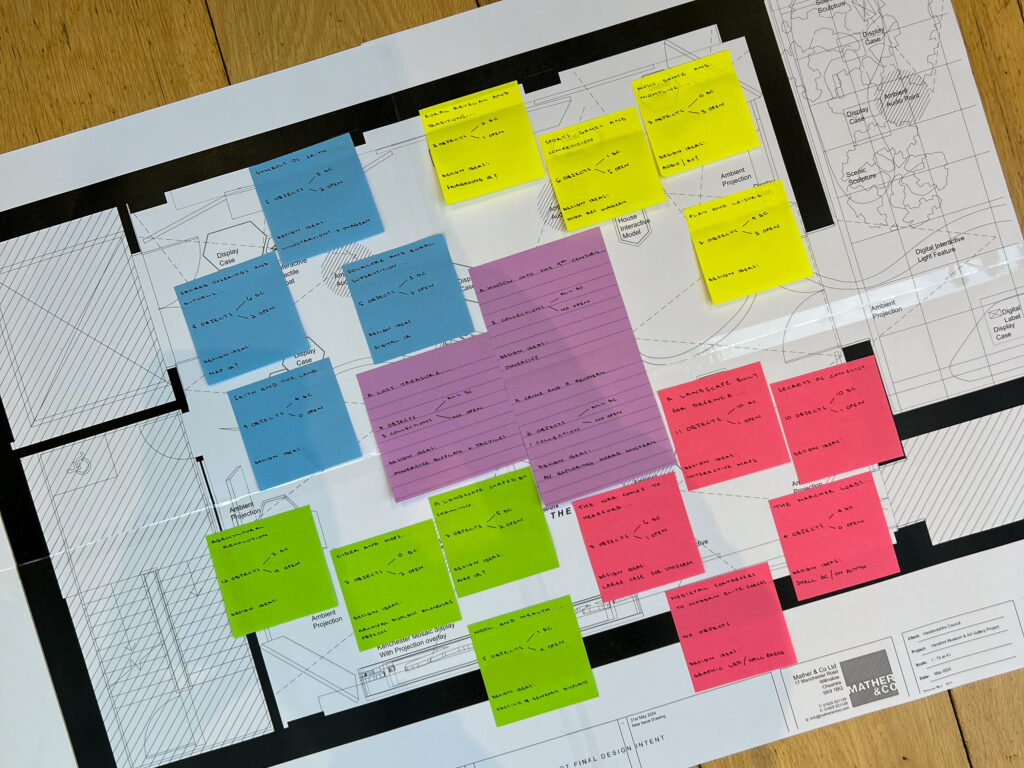

Projects tied to strong local identity are also rarely smooth - they attract competing expectations from funders, councils, historians, community groups and visitors. The design process becomes a way of translating that tangle into something coherent and welcoming.

Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings offers lessons in how to manage this well. The site, the world’s first iron-framed building, had decades of industrial grit, social history and modern regeneration politics bound up in it. The design team treated those tensions as material, not obstacles. The building’s scars were left visible - modern interventions were deliberately distinct rather than disguised.

By doing so, the Flaxmill tells several truths at once - the pride of local workers, the innovation of early engineers, and the uncertainty of post-industrial change. Visitors aren’t told what to think, they’re simply invited to consider how all those threads connect.

A few principles often help to hold such projects steady:

- Start wide, narrow later. Early consultation should welcome contradiction – the editing comes later.

- Treat heritage as a living thing. Let evidence of use, repair and reinvention stay visible.

- Aim for empathy, not consensus. A museum can’t please everyone, but it can make everyone feel heard.

These ideas sound simple but they demand time and trust, two things often squeezed by funding cycles. Still, they make the difference between a building that’s simply admired and one that’s loved.

From local story to shared experience

Museums grounded in place don’t have to feel insular, in fact, the more specific the story, the more universal its appeal tends to be. Visitors connect not because they share the same history, but because they recognise emotion - struggle, ingenuity, belonging, loss.

That’s the thread linking the Pankhurst home to the Flaxmill - both are deeply local and unmistakably human. One turns a terraced house into a platform for women’s voices, whilst the other turns a factory into a symbol of endurance and reinvention. Each honours where it stands while inviting people from anywhere to care about it.

Design, at its best, can hold that tension - between pride and openness, between remembering and re-imagining. Getting it right isn’t about smoothing out the politics of place but allowing space for them. When a museum achieves that, it becomes more than a visitor attraction - it becomes a mirror in which a community sees itself, with all its edges still intact.