Somewhere along the way, we’ve convinced ourselves that it’s perfectly reasonable to ask experienced agencies to do a chunk of the work before they’re paid a penny for it. Not just outlining an approach, but producing proper creative thinking – ideas, concepts and direction. That work costs real money - we’ve spent small fortunes in the past on pitch processes, sometimes with costs above £50k (yes, really). It’s little surprise that agencies increasingly question whether it’s worth the time and disruption involved.

One thing’s for certain, there’s no such thing as a free pitch. Every one of them costs money, time, people and headspace, pulling senior teams away from existing client work and creating pressure elsewhere in the business. The more creative the ask, the higher the investment required.

What’s often overlooked is the different ways risk is experienced during a pitch process. Design agencies invest significant time, money and expertise with no guarantee of success, while clients solely balance the process alongside wider organisational priorities. In that context, clients paying for pitching becomes a more balanced exchange, helping both sides share the risk from the outset and build more sustainable, long-term relationships.

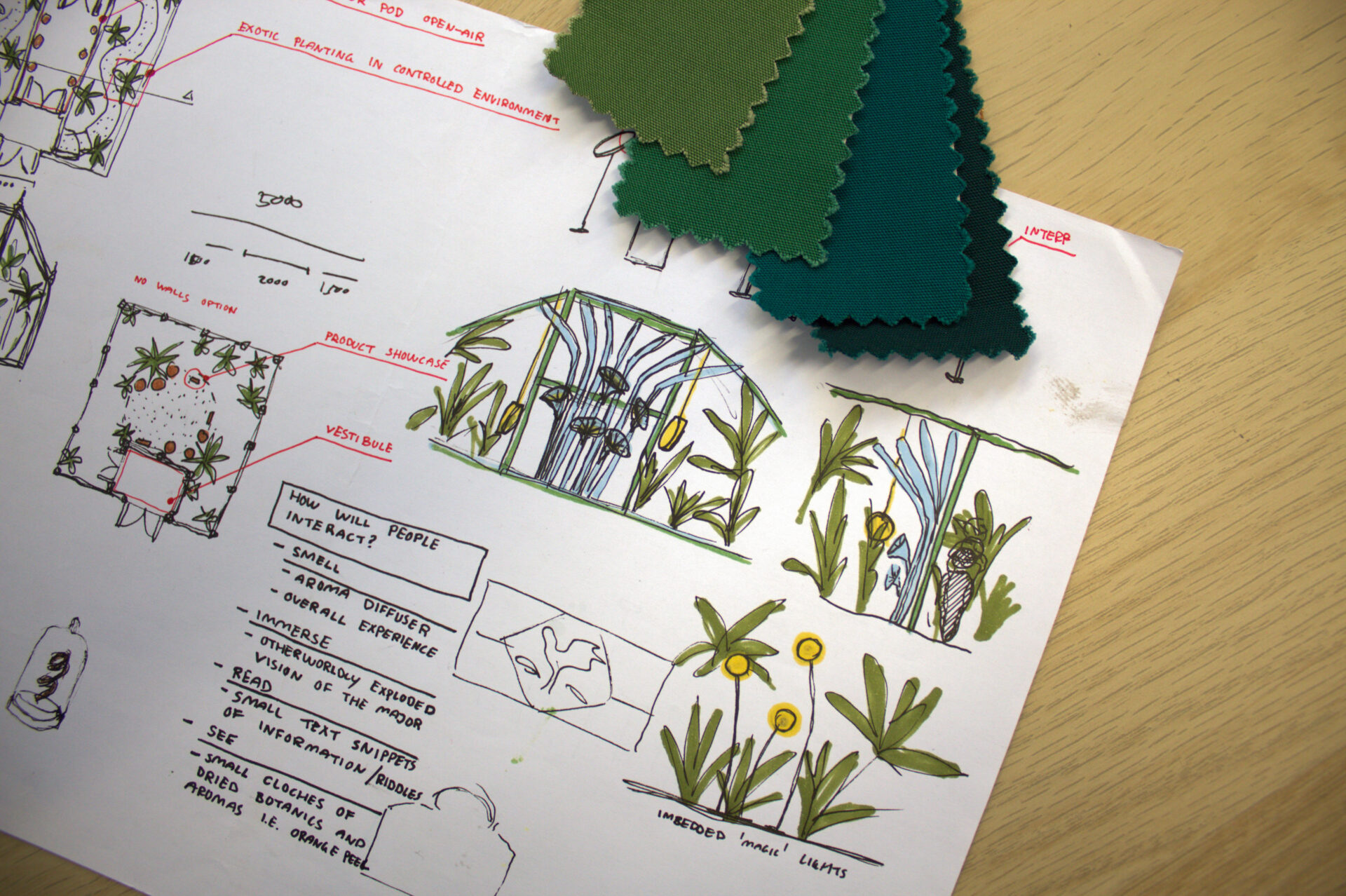

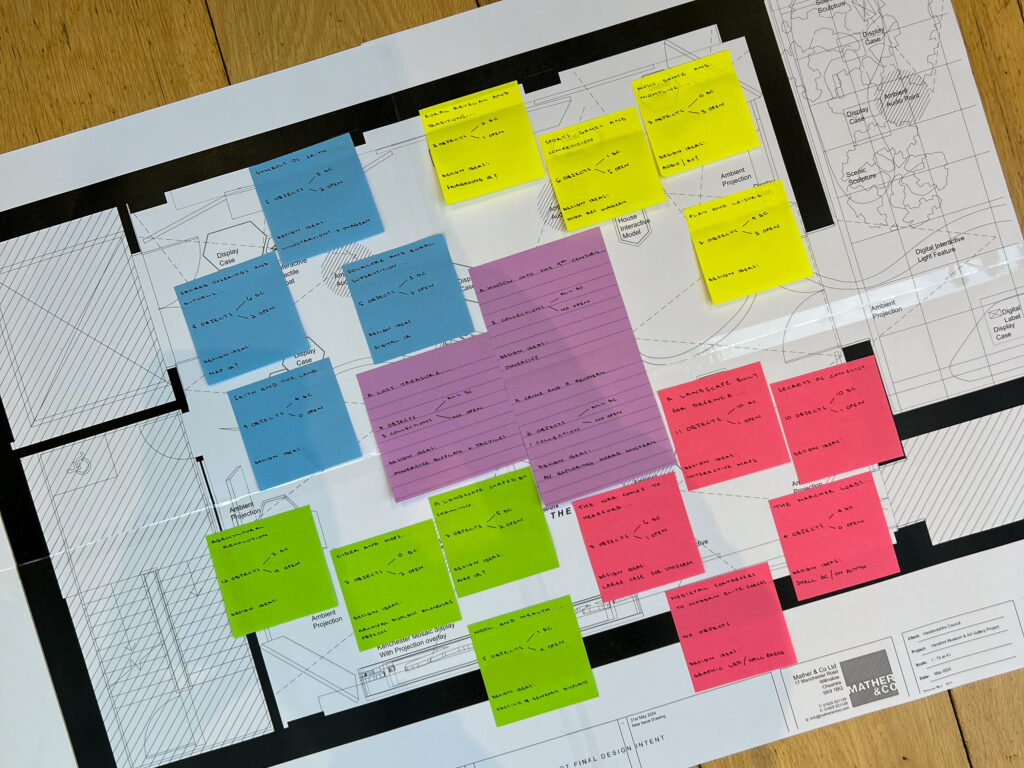

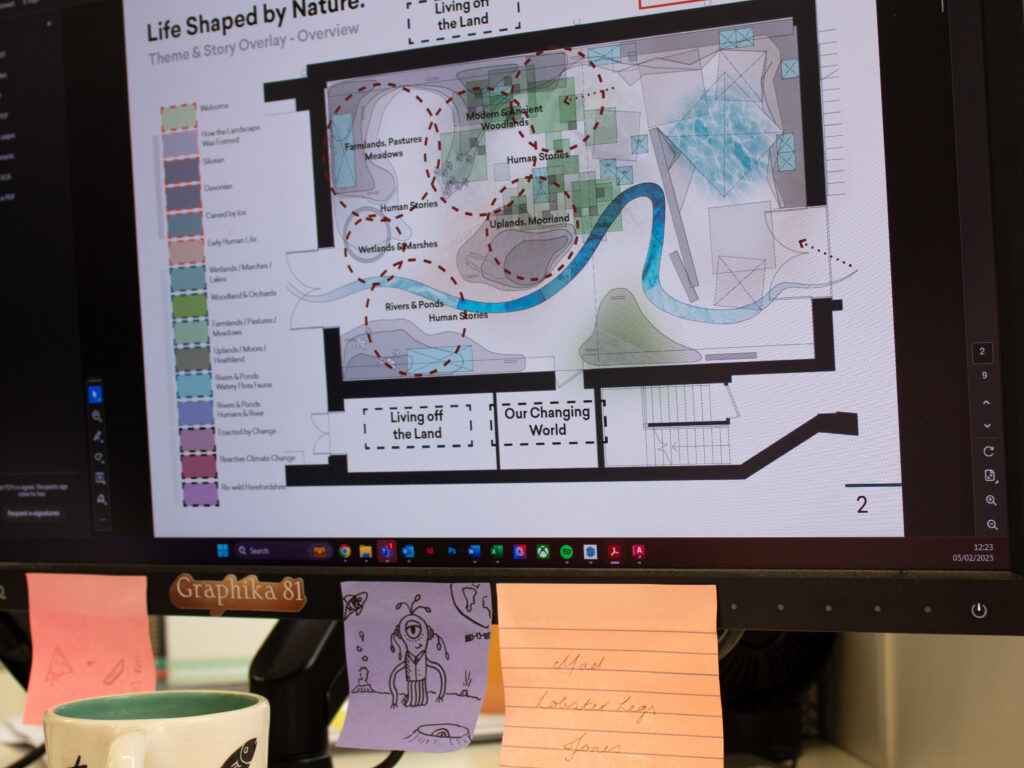

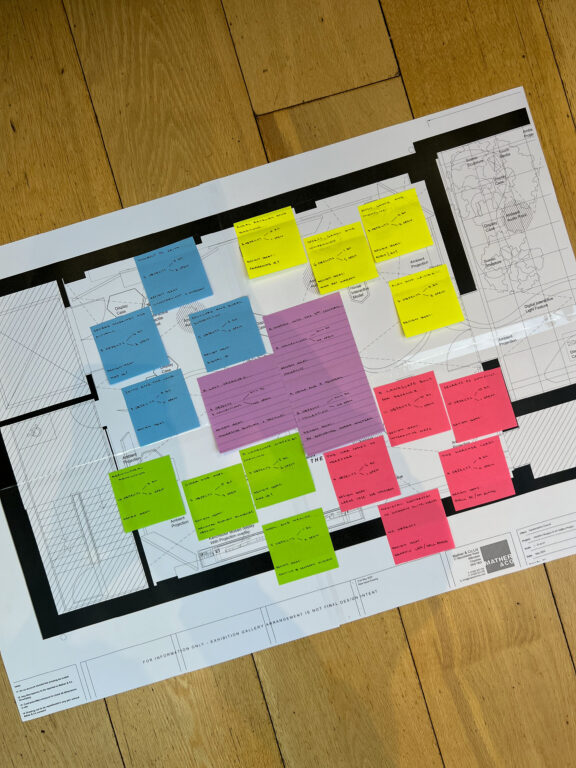

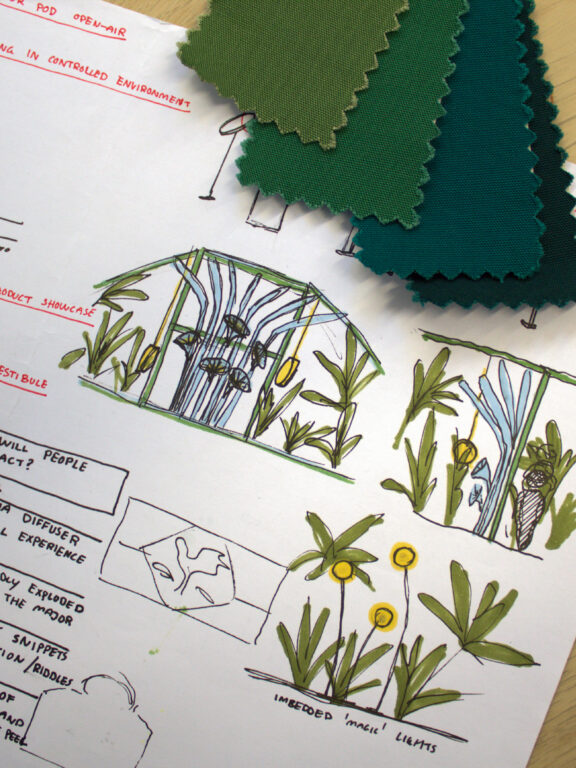

The moment a potential client says, “We’d like to see some creative,” that’s when the real cost begins because creative doesn’t appear by magic. To do it properly, we need to understand the brief in depth – the audience, the politics, the content and the constraints. You’re effectively closing in on designing the solution, just without being paid for it and without any guarantee of winning the work. That upfront thinking – the ideation – is the hardest and most valuable part of the job, yet it’s the bit people most often expect for nothing.

It’s mad when you think about it - yet many professions, including creatives, architects and designers fall into line most of the time and commit to the process. However, when designing a visitor attraction or experience, the work is so complex and detailed that there are no shortcuts to a meaningful vision.

Another thing we don’t talk about enough is what happens when five or six agencies – sometimes more – are asked to pitch at the same time. At that point, it’s not just about comparing suppliers - it inevitably becomes a comparison of ideas. Even with NDAs in place, ideas have a habit of sticking. Directions resonate, themes overlap, and before long the final outcome can feel like a blend of multiple pitches. It’s rarely deliberate or malicious, but it does raise questions about how fair or effective the process really is, and whether anyone ends up getting the best result.

At some point, experience and references should count for more. If an agency has decades of work behind them, a strong track record in a particular sector, and projects you can go and see for yourself, why are they still jumping through the same hoops as everyone else?

There are better ways to choose creative partners than asking multiple agencies to develop speculative ideas, which are often subjective when the process is design-only focused. A short, paid strategic or exploratory phase – an opportunity to explore the potential – allows both sides to properly understand the brief, test collaboration, and decide whether there’s genuine chemistry before committing to full delivery.

I’m not saying pitching should disappear altogether, but I do think pitches should be remunerated, even if only at cost and expenses. If a project is of significant value, then the budget – at least for commercial organisations – should include something for the pitch stage. Not to cover everything, but to acknowledge the real cost of upfront thinking, particularly where creative work is involved. It would also lead to better thinking, clearer recommendations and more honest conversations where agencies would challenge assumptions, flag risks and explore bolder opportunities.

Where public-sector tenders are concerned, there are improvements that could be made there too. Too often, tenders are poorly written, lack sufficient detail, and rely on ambiguous scoring criteria. Designers are asked to respond creatively without a clear understanding of the client’s vision, while being judged against criteria that are open to interpretation. When briefs are unclear, scoring inevitably becomes subjective rather than genuinely evidence-based. If public tenders genuinely aim to secure the best team for the project, then the quality of the brief, the clarity of the criteria, and the evaluation process itself deserve as much scrutiny as the responses they generate.

What I find most frustrating is the irony that millions can be spent on delivery, while nobody wants to pay for or more deeply consider the thinking that makes it successful in the first place. If thinking is wrong, the direction is wrong, and the whole project suffers.

Good ideas don’t come cheap – and they certainly don’t come free to those of us pitching.

If we want better projects, better partnerships and better results, it’s probably time we stopped pretending that unpaid pitching is just ‘how it’s always been done’ – and asked whether it’s really the best way forward.